Workforce housing

Most of the new people moving to South Dakota in recent years are moving to the Sioux Falls area.

The latest census data shows that of the 72,000 people who moved to South Dakota in the last decade, about 67 percent came to the four-county area around Sioux Falls. But those newcomers – and many of the existing residents – are facing the same dilemma: Where are we going to live?

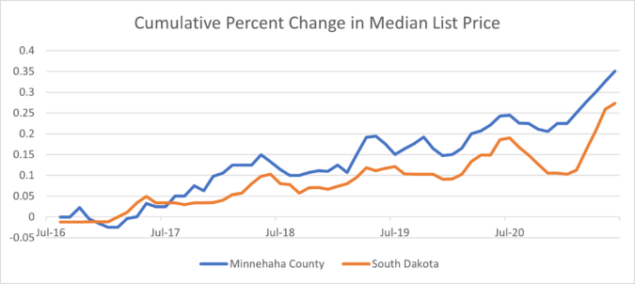

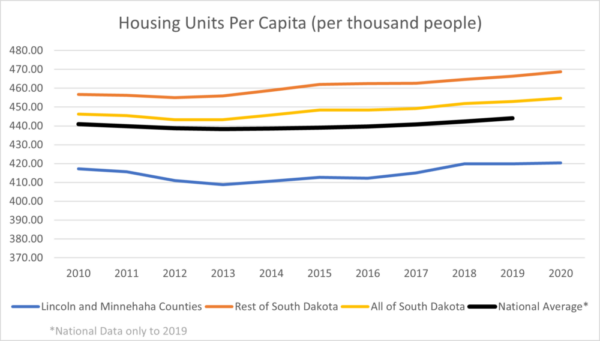

Housing supply isn’t keeping up with demand in Sioux Falls, as the metro region faces rising construction prices, rising sales prices and rising rental costs. One of the groups facing the greatest challenge right now are those that fall into what’s being called “workforce housing.”

Those challenges haven’t gone unnoticed in the state. Over the last year, a workforce housing committee organized by state government has met to study the issue. In December, Gov. Kristi Noem proposed a $200 million spending plan to help address housing shortages in the state. That plan then worked its way through the legislature and ultimately – with some tweaks – was signed into law.

Meanwhile, locally, the city is also implementing programs to help with housing shortages, and private developers have had a seat at the table all along the way.

While the problem is becoming increasingly well-known and understood, the solutions aren’t as simple. And it’s going to take an all-hands-on-deck approach, said Jake Quasney, chief operating officer for Lloyd Companies.

“As business owners, that’s an area we’ve got to find a way to focus some energy around in our community,” Quasney said. “If we can’t create housing for people, eventually, they’ll stop moving here, and eventually, employers can’t continue this trend of coming here.”

What is workforce housing and how big is the need?

Workforce housing (or, as Gov. Kristi Noem describes it, “career housing”) doesn’t have a formal definition in the state, but there’s a general understanding of what it means, said Debra Owen, vice president of government relations for the Greater Sioux Falls Chamber of Commerce. That is that workforce housing is housing aimed at helping people whose incomes make them ineligible for government assistance for low-income housing, but nonetheless they are unable to afford housing or are in a situation where they’re house-burdened.

“This is for the young couple who’s trying to manage day care and a house payment, or the person who is working full-time but still can’t afford a house,” Owen said. “That’s the gap (Noem) was trying to fix.”

Jeff Eckhoff, director of planning and development services for the City of Sioux Falls, says another way to look at it is a simple equation of income vs. expenses. A general rule, Eckhoff says, is that 30 percent or less of household income should go to cover housing. If the percentage is higher than that, a person is considered “house-burdened.” That’s also the standard set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

So, just as an example, take a couple in which each partner makes about $15 per hour. Their combined household income – assuming they both work full-time – would be about $62,400 annually. Looking at 30 percent of that income divided monthly over a year, that couple could reasonably afford housing costs of about $1,500 per month. Keep in mind, with Eckhoff’s equation, that 30 percent should also cover all utility costs.

The math gets trickier when the person is an individual without a partner to contribute to the housing equation. At $15 per hour, a person would be house-burdened if they spent any more than $780 per month on housing.

Sioux Falls’ median rent price as of May 2022 was $970 per month, a 14 percent increase year-over-year, according to the latest data from rental listing site, Dwellsy.

What’s the scope of the need?

Despite understanding what workforce housing looks like, the scope of the need for workforce housing isn’t fully understood, Eckhoff said. That’s largely because it’s difficult to track without knowing every person in town’s income vs. housing expenses.

“It’s probably bigger than any of us could imagine,” Eckhoff said. “If you think about the number of people in housing who’re paying more than 30 percent … that entire group would be in this category.”

That said, the state Legislature’s Workforce Housing Needs interim study – which included several legislators from Sioux Falls – estimated about 7,000 housing units are needed in the city. That group also estimated a more than 14 percent decrease in housing affordability.

What are the challenges for developers?

The biggest obstacle is cost. Quasney gave the example of the cost Lloyd Companies is incurring to build one housing unit today compared to the cost even just a few years ago.

“(Four years ago) it would cost me about $90,000 per unit,” Quasney said. “Today that same unit is costing me, depending on what community it’s in, between $130,000 and $145,000. So costs have jumped that much.”

And that’s setting aside the cost of land, Quasney said, which has also increased about 20 percent. The saving grace for developers seeing these rising costs has been the low interest rates, he added, but now that’s changing, too, as the federal interest rates increased again in June.

“At the end of the day, there’s only so many levers you can pull,” he said. “So, if rents don’t meet the costs, you can’t build it … but at some point we know that, along with everything else, it’s hitting our residents. It’s hitting our employees. The problems are going to keep getting worse.”

Developers also face uncertainty on when help from the state may come through for them as lawmakers weigh questions surrounding how to spend $150 million in state funds allocated for housing.

What is the state doing to help?

Gov. Noem’s plans to spend $200 million on workforce housing saw some resistance in the legislature, Owen said.

“It was never a guarantee that this plan would go through,” Owen said. “But there were a lot of us working on it together.”

The collaborative work paid off, and ultimately, the governor signed House Bill 1033, appropriating $150 million in state general fund dollars and $50 million in federal COVID relief funds to help pay for the infrastructure costs associated with housing construction. The hope is by paying some of those infrastructure costs, developers will be able to face lower construction costs and thus make the housing more affordable for buyers and renters.

With those funds, though, there are still some unanswered questions. The $50 million in federal funds will be made available starting July 1, 2022. Applications are being processed through the South Dakota Housing Development Authority.

There is work yet to be done in determining how developers will access the remaining $150 million in state dollars. The legislature still needs to decide on how to define workforce (or career) housing and how to earmark the money specifically for that need. Until those decisions are in place, the money is stuck in a holding pattern.

There’s a chance the legislature will resolve how to spend that $150 million yet this year, but if they don’t, developers may have to wait until the 2023 session for clear answers.

What is the city doing to help?

Closer to home, the city also has programs in place to help address housing needs.

Sioux Falls received some direct federal funding from the American Rescue Plan Act, money aimed at helping the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic. That funding, along with some city funds, has left $6.5 million in one-time funding for various housing programs, Eckhoff said. Those funds include programs that offer mortgage assistance to first-responders, police officers and people in similar positions. There have also been funds made available for home repair and sidewalk repair for people in housing situations where they don’t have the extra money for those necessary repairs, Eckhoff said.

In addition, the city has tax-increment financing (TIFs) available for developers who are willing to create a minimum of 30 housing units. The developers must have at least one-third of those units at 75 percent of the income requirements for the state’s first-time homebuyers program. Another third must be at no more than 100 percent of those income requirements, and the remainder may be up to 110 percent.

There’s a similar TIF opportunity for multi-family housing to help with land acquisition. Eckhoff said the city is working on a program that hasn’t yet been released that would provide loans for developers who put together multi-family units, provided those developers keep apartments at an affordable rate for the next 10 years. More details to come on that as it rolls out.

What role do developers play in finding solutions?

For their part, developers in the area are already doing what they can to help. Several developers and community stakeholders were part of a local workforce housing committee that met regularly last summer to work through the issues and brainstorm solutions.

Many went on to testify to the Legislature’s workforce housing interim study committee. They laid out the story of housing challenges in the Sioux Falls metro area and then brought forth suggestions for pragmatic tweaks to current programs, along with possible new solutions. They urged the legislators to think big and embrace long-term sustainable solutions for workforce housing that benefits both large and small communities across the state.

Owen credits these Chamber members for clearly illustrating the importance of government help in addressing housing shortages.

“We have a community that’s willing to share our successes to help move South Dakota forward, and that’s leadership in my opinion,” Owen said.

That leadership also shows up when looking at current development in Sioux Falls. Despite challenges, developers are still continuing to build. In 2021, the city broke the all-time record for building permit valuations with a more than $1 billion year, and no small portion of that was housing.

So far in 2022, the city was already on track to beat the last two years in the number of residential building permits issued. In 2020, the city approved permits for about 2,700 units. That number jumped to 3,100 in 2021, and as of the end of May, the city had already seen about 2,500 permits for 2022.

At Lloyd Companies, Quasney said they’re working to build anything and everything they can afford to, and they’re applying for TIFs to help lighten their load.

“We’re really trying to do a lot of larger developments between 150 to 250 units in a project, so we can get some efficiencies and try to drive those costs down,” Quasney said.

What happens next and what challenges lie ahead?

One of the biggest questions right now is how and when the $150 million in state funding will be made available to developers. But even when that money comes through, city officials and developers agree it won’t be a silver bullet to fix the housing needs in the community. That means government and industry will have to continue to put their heads together to find solutions.

“We’re going to have to get creative with solutions that take advantage of existing housing stock,” Quasney said.

Meanwhile, Eckhoff said the city has a continued role to play, albeit a cautious one.

“As a government entity, you always have to be a little careful about putting your thumb on the scale too much because, at the end of the day, the market has to work,” he said.

And he expects the wins along the way will be small ones. “There’s no home runs,” he said.