Fifty years of partnership

How business leaders brought EROS to Sioux Falls

Whatever is required, we will do it.

“We’ll give the land.”

When Al Schock blurted out that promise during a trip to Washington, D.C., in early 1970, it tipped the scales in the city’s favor: Sioux Falls would be the future home of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center.

Schock and his fellow Sioux Falls boosters were lobbying for a program that was full of promise but largely untested. They couldn’t have anticipated that 50 years, nine satellites and hundreds of employees later, the EROS Center would host one of the largest image archives in the world, with a staggering 73 petabytes of data. Or that the Landsat program and EROS science products, ranging from fire and forest monitoring to urban heat mapping to agriculture and vegetation analysis, would have an annual economic impact of $3.45 billion worldwide, with $2.06 billion in the United States alone.

It’s no stretch to say that these remarkable accomplishments would not have come to pass without the hard work, creativity and determined attitude of a group of Sioux Falls business leaders. EROS—with its educated workforce, scientific prestige and economic contributions to the community—became the first gem in a long string of successes for economic development in Sioux Falls.

A satellite trained on Earth

In the post-Sputnik mad dash to explore space, NASA was focused on the moon. But the U.S. Geological Survey saw equal promise in the early Earth images taken by U.S. astronauts. Scientists William Fischer and Charles Robinove pitched the idea of a fixed-orbit satellite trained on Earth’s landscapes, collecting consistent images around the entire planet to observe change.

USGS chief William Pecora sold the idea to Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, who essentially created the EROS program via press release in 1966. NASA agreed, in 1968, to build the Earth Resources Technology Satellite (ERTS-1) satellite and launch it in 1971 or 1972. (In 1975, the ERTS missions were renamed Landsat, just in time for the launch of Landsat 2.)

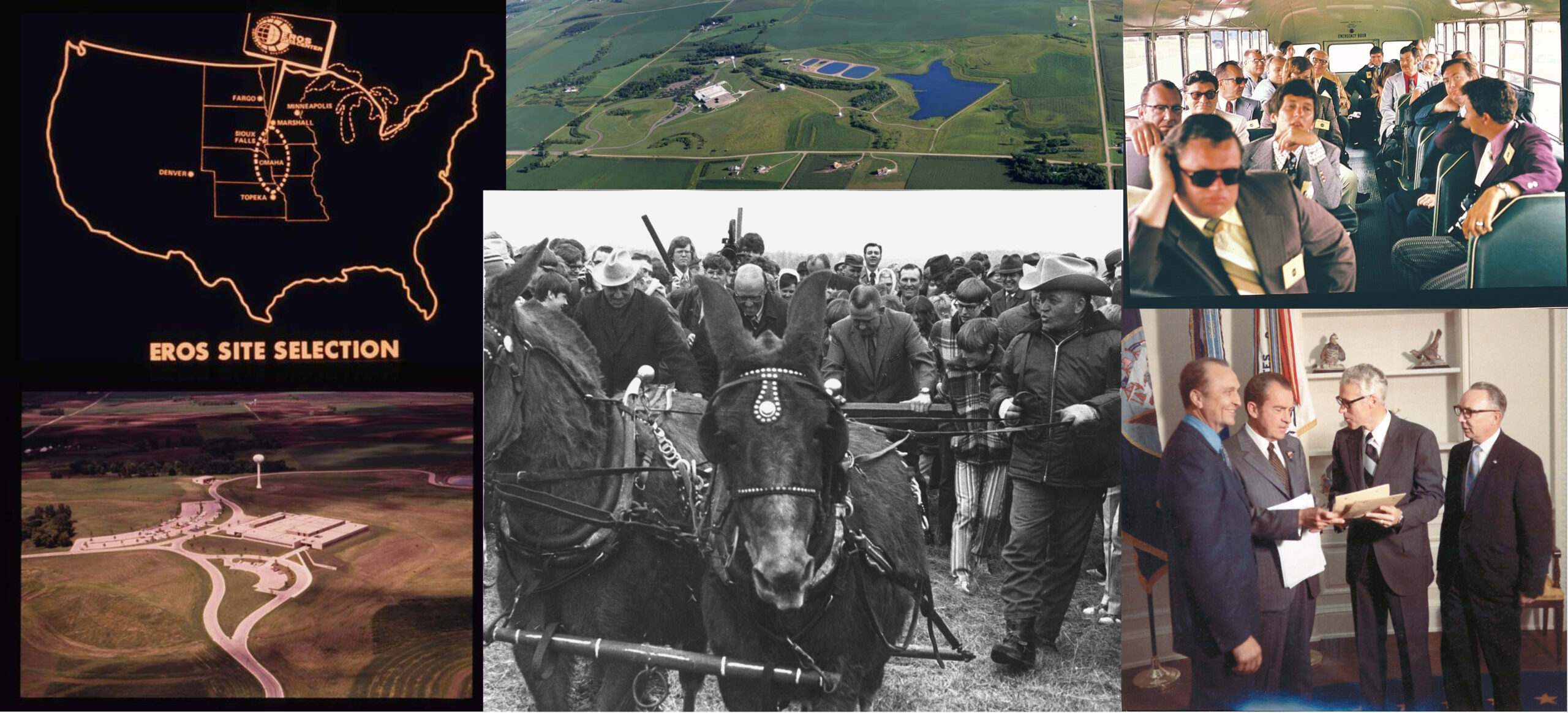

Once the Department of the Interior determined the center of the 48 contiguous states would be the best place for satellite reception, cities from Topeka, Kansas, to Sioux Falls started competing to host a space-age, high-tech data center to develop, catalog and interpret what was estimated to be 25,000 images in the first year.

The Sioux Falls Chamber of Commerce and Sioux Falls Development Foundation led lobbying efforts. South Dakota had an edge with its high-powered congressional delegation. Senate Minority Leader Karl Mundt, a personal friend of then-President Richard Nixon, and Rep. Ben Reifel both were the ranking members of their respective Interior Appropriations Committees. They worked to secure funding for the project.

On March 30, 1970, another preemptive press release, this one from Mundt’s office, proclaimed that Sioux Falls had been chosen—somewhat before it was 100% official. Now the hard work of making the center a reality began.

Operation Ground Shot

In addition to lobbying for the EROS Center, the Chamber and Development Foundation had long wanted to build an industrial park to attract more businesses, so they tied the two projects together, launching Industrial Development Week on April 23, 1970. Pecora spoke at the kickoff event, and a traveling display was created with exhibits about EROS, other local industries, samples of moon dust and a South Dakota flag that had been carried to the moon by Apollo 11 astronauts. For a $2 donation, people received a button proclaiming them as “Sioux Empire Builders.”

Next came Operation Ground Shot. On May 21, 1970, dozens of members started a fund-raising drive in the business community, with a goal of raising $390,000 to buy the land for EROS and the industrial park. By the end of July, $480,000 had been raised—and now a site needed to be found for the data center.

From Pecora, organizers had learned the specifics. The EROS center would have to be within 10 miles of the airport and meet soil stability and water requirements. It would also have to ensure low electronic interference. And instead of the 10 acres Schock had envisioned when he made the offer of land, the site itself would require 100 acres, plus a 200-acre buffer zone! His response exemplified the attitude of the coalition working on the project: “Whatever is required, we will do it.”

And that’s just what they did. After 318 acres were purchased from the Froseth and Hegge farms, federal funding to build the center stalled in Washington, D.C.. Sioux Falls devised an innovative solution: the Development Foundation would secure the $5.5 million loan, build the center, then lease it back to the federal government for 20 years until it was paid off.

Breaking new ground

There was no template for how to build a photo processing and interpretation facility on this scale. Local architectural and engineering firms Spitznagel Partners Inc. (now TSP, Inc.) and Fritzel, Kroeger, Griffin and Berg designed the building and infrastructure, including five processing pools to ensure that photochemicals didn’t enter the groundwater system.

That “from scratch” quality permeated much of the activity required to make EROS a reality:

- When farmers were worried about potential electrical effects and land price issues, business leaders helped county commissioners and EROS chief Glenn Landis communicate about rezoning—which eventually passed with no protest.

- The new building would not be ready in time to begin processing Landsat 1 photos, so the Soo Hudson building at 10th Street and Dakota Avenue became the Downtown Office. No telephones or typewriters were present for the office’s opening September 28, 1971, but it eventually housed the film, photo processing equipment and the IBM 360-30 computer—with a memory capacity of 64,000 bytes.

- A federal hiring freeze posed problems for hiring the workers needed, but the Job Service of South Dakota coordinated training programs for unemployed people using the Work Incentive Program. Fifteen new employees learned the complexities of photo processing in an intensive six-week program.

Schock staged the actual groundbreaking ceremony with characteristic panache. Pecora, now Undersecretary of the Interior, Merlyn Veren (who lobbied for the project in Washington, D.C.) and EROS director Glenn Landis helped guide a mule-drawn plow to turn earth at the EROS site on a cool morning, April 14, 1972.

During the ceremonies, Fischer, one of the scientists who conceived of EROS, summed up the massive scale of the project: “It is the largest Earth scientific experiment ever undertaken by man, and possibly the most significant.”

Landsat 1 launched on July 23, 1972, from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. A delegation from South Dakota included Governor Dick Kneip and many of the local supporters who had worked to make EROS a reality.

The world comes to Sioux Falls

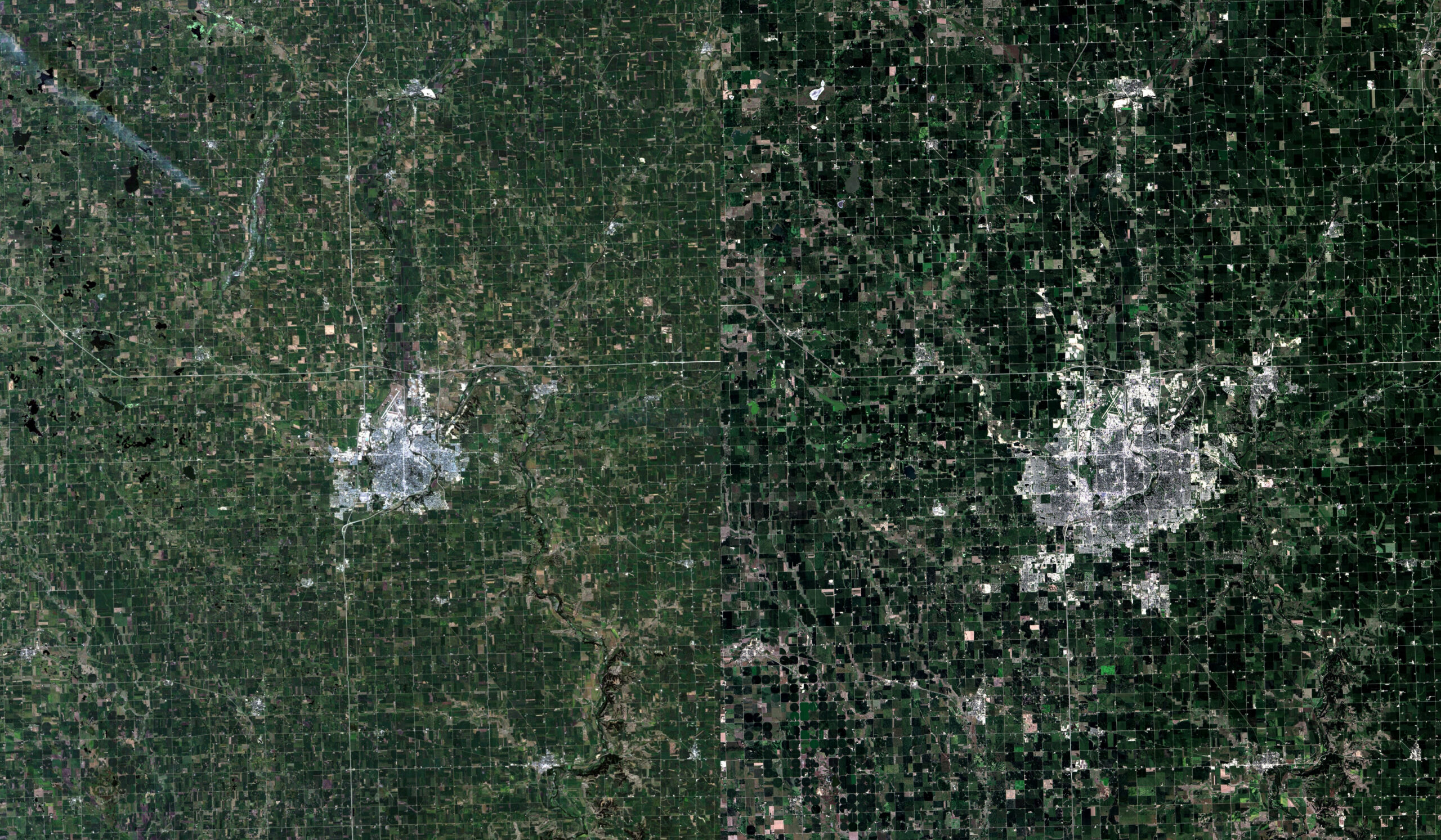

Every 18 days, Landsat 1 recorded a complete scan of the entire Earth, and that ability to consistently detect land change over time across the globe was unprecedented in human history. Scientists immediately saw the possibilities for mapping, agriculture, disaster relief, locating minerals, forestry and dozens of other applications.

Even before the EROS Center opened its doors, 33 researchers from around the world came to Sioux Falls for the first international training course in June 1973, learning how to read satellite imagery. These workshops continued to bring in visitors from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe twice a year through the late 1980s, offering not only training but also imagery useful in their home countries.

Along with international visitors, officials and scientists from state and federal agencies also flocked to EROS in those early years, all hungry for training and data. By April 1975, for example, projects included the South Dakota Land Use Project; flood and flood-plain analyses; an inventory of shelterbelts in the Plains states; an environmental evaluation of strip mines; and assistance for the Algerian Ministry of Hydraulics to establish remote sensing planning.

Scientists and engineers recruited from Berkeley and across the country raised their families in Sioux Falls and contributed to dozens of monitoring, mapping and archiving programs housed at EROS. Today, the more than 600 EROS employees contribute to the Sioux Falls and South Dakota economy in their own right but also via the value of the unparalleled archive and its scientific products they maintain and study.

- The archive contains millions of images of aerial photography, both before and during the satellite era; EROS is the federal repository for those resources.

- Space photography, from Apollo to Skylab, also is housed at EROS.

- In 1996, EROS received 800,000 declassified spy photo-reconnaissance satellite images collected from 1960 to 1972.

- A physical copy of every map ever created by the USGS also is stored at EROS.

But the real jewel of the archive is the millions of images of Earth faithfully recorded for the past 50 years by Landsat. This valuable satellite data, now accessible at no cost to scientists and land managers across the globe, acts like a time machine.

Next for EROS and Sioux Falls

Today, Landsats 8 and 9 work in tandem to give a complete picture of the world every eight days. With the anticipated launch of Landsat Next in 2030, a trio of satellites with enhanced spectral imaging will narrow that window to map Earth every six days, creating even more societal benefits.

The unparalleled archive data, along with EROS scientists’ industry-defining satellite imagery calibration and validation techniques, also help ensure the longevity of the center’s contributions to the world in general and Sioux Falls in particular.

In the 50 years since the EROS center opened its doors, Sioux Falls has tripled in population, while the workforce at EROS has doubled. Time and again, the business community has supported the center, hosting anniversary celebrations over the decades and even participating in a ceremonial burning of the original 20-year lease in 1994. In turn, EROS’ scientific cachet is tapped by economic developers to attract businesses and people to the metro area.

It’s a partnership that couldn’t have happened without the dedication and innovation of visionary local leaders—and one that seems destined to bear fruit for years to come.